I'm a sucker for books that play around with the physical form of the novel. Whether The Raw Shawk Text's ASCII-art-esque storytelling, or House Of Leaves' daring adventures in typesetting, I'm immediately on board for whatever crazy tricks an author wishes to pull. Fortunately, in all cases so far the actual book has turned out to be really good, and not just a novelty. That trend continues with S, aka The Ship of Theseus, which is by far the most ambitious work I've seen yet in this regard.

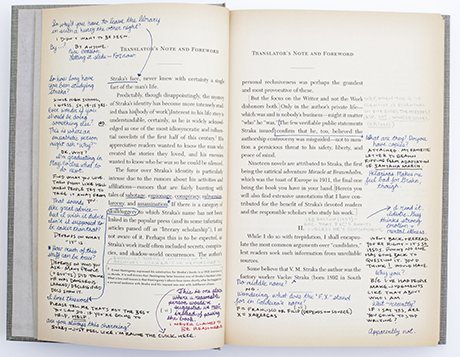

The book presents itself as a timeworn novel from an academic library's stacks, complete with age spots and circulation stamps. The text of the book tells a story of its own, a surprisingly dire and macabre one, but the real story is the one that takes place within and outside the text. Two readers start leaving notes in the margins of the book, eventually starting a dialogue and, eventually, a relationship that grows between the two of them as they bond, initially over a shared love of the book and eventually for... well, more reasons. But that's not all! The book is literally stuffed with other materials, like postcards with foreign stamps and maps drawn on cocktail napkins and articles cut out from the campus newspaper and lengthy handwritten notes.

I am thoroughly impressed at the engineering work required to assemble this thing - I kept worrying that all this stuff would just fall out of the book, but somehow they've been able to construct it such that they remain securely in place until you're on that page, at which point you can easily remove them (nothing is physically attached), inspect them, and then return them securely in place. I have a hard time visualizing the production of this book. You can't make cocktail napkins on a printing press, so did they hire an army of child laborers to put this together? Or some kind of fantastic Rube Goldberg-esque machine that folds and stamps and inserts all this stuff? Even the marginalia seems tricky: it's all handwritten, not typed, so there must be an insanely high-resolution scan of this thing to get all the ink blots and stuff right. Heck, even the "ink" itself requires effort: particularly heavy blocks of black ink appear to "bleed" through to the opposite side of the page, even though I'm pretty sure that they're actually reversing and re-applying the images on the opposing side to create the effect. It's very well done!

It's also interesting from an intellectual-property perspective. This might be the first book I've read that can't be pirated; or at least the first one since my days with pop-up and scratch-and-sniff books. Even if someone were to laboriously scan this book into a PDF (you couldn't OCR it), you'd miss a significant portion of the story without the inserts. Anyways. I'm fascinated by the idea that, while advancing technology has harmed the publishing business in many ways, in this particular case it seems to have produced a book that "protects itself" in a really unique way.

The story itself is... well, it's complex! There are multiple plotlines taking place, both within the book and within the "real world", over a long period of time and with different groups of characters. Many of the stories feel emergent, as when the two protagonists (Story A) are trying to glean the text (Story B) for clues about what real-world events the story is allegorizing (Story C). I earlier mentioned House of Leaves, which is a pretty good exemplar of this type of storytelling: that book had about five different layers of reality/storytelling, from the in-universe-fictional film The Navidson Record to the in-universe-real book House of Leaves to the primary authorial footnotes on HoL to the secondary editorial footnotes to the tertiary publishers' footnotes. Each of these should be a one-directional remove in storytelling (one step up the Wick in Anathem terms), but what was uncanny in HoL was how ideas in fiction would pollute/infect supposedly-real events. That same kind of interplay is on display in S: reading a book initially seems like one of the safest activities a human can undertake, but the contents of that book affect the thoughts of its readers, and eventually starts to steer their lives in a very different direction.

Another book I often thought of while reading this was Pale Fire. There are some strong surface resemblances, as in both cases there's a fictional work under consideration, and the actual story is happening in the "literary criticism" being performed on it. The big difference is that in Pale Fire, that criticism happens through exposition, while in S, it happens through dialogue. The two protagonists each offer their own theories, test one another, find supporting evidence, discover links between texts, and in general collaborate on a better understanding of the work (in contrast to Kinbote's monomaniacal insistence at projecting his own vision over every aspect of the work). As a proud member of the Professional Organization of English Majors, this kind of story-about-analyzing-stories makes me giddy.

The timelines are really well-done, too. For all the talk about how modern society has been dumbed down, I actually think there's a lot of evidence that large sections of our culture are embracing extremely complex works: movies like Pulp Fiction and Memento were initially hailed as unprecedented experimental works for the way they interrupted our conventional view of timelines, but today nobody bats an eye at this sort of temporal play. Certainly, our television shows have grown far more intricate than in the past (thanks in no small part to JJ Abrams himself with Lost's vast and evolving mythology), and my generation, which grew up on video games, are comfortable with all sorts of ideas about agency and fluid perspective and unreliable narration and branching storylines.

MINI SPOILERS

The way it's done in S is through differently-colored pens: in the first couple of pages, you start to recognize the protagonists' handwriting (one writes in cursive, the other in print); over time, you come to understand how the different colors indicate different periods of time when each was writing. Notes in pencil are old, from when Eric was in high school; blue and black pen are from when they're first discovering each other and starting to investigate the book; yellow and green are after they've come to trust each other and are starting to make contact in real life; red and purple come after they've made contact with Filomela and are being pursued/harassed by their enemies; and a final set in all black comes after they've made their escape. (Touchingly, you realize this is because they're now living together and therefore can share the same pen.)

So, on a single page in the book, you might have events taking place in up to seven different timelines: VMS's original text, Filomela's later footnoting, and all of the various dialogues between Eric and Jen. Each newer layer can comment on an older layer. On the next page, you'll get continuations of all those timelines: so the yellow text on this page was written after the blue text on this page and the blue text on the next page, but before the red text on the previous page. It seems really complex at first, but I was surprised by how swiftly I was able to grok it and keep it straight. It definitely helps to only have two participants; it would probably grow exponentially more difficult to track with additional writers.

I should note here that I've deliberately stayed away from any and all online discussion of the book; I'm sure that I'll jump into it after publishing this post, but I wanted to get down my initial "pure" reactions before seeing what other people have come up with.

There's a ton of interesting stuff going on in the book, but one of the most intriguing is the codes. Eric and Jen first start collaborating through their attempts to find and solve the messages that FXC has hidden in the book. This is done well, with initial descriptions of things they've noticed, a few ideas tossed out and developed on, an announcement of the discovery, and finally the full translated message, followed by a discussion of what it means. This is repeated in later chapters, though less time is needed to describe what they're doing for subsequent ciphers. Near the end, though, there are several chapters with discussions about how they are convinced there is a code, but haven't been able to find it. I strongly, strongly suspect that there actually is one in there, and have no doubt that enterprising readers have discovered and decrypted it. I was in a hurry to get through the book so I didn't spend any time trying to suss it out myself, but I'll probably take a crack at it myself before hopping online to see if and what other people have found. (My one hunch so far has to do with place names being important in one chapter's footnotes, but we'll see if that's relevant or not.)

Codes aren't the only unexplained mystery in the book. One big one that surfaces early on, and remains present but is never resolved, is who else is reading the book. Throughout the book, one or both of them (but I imagine usually Jen) will draw a tiny sketch, the sort of thing that you would doodle in your college notebooks. In one early section describing the mysterious "S" symbol, a stylized version appears in the margin. Each thinks that the other person drew it, and they get freaked out when they realize neither did. So, someone else drew it, so someone else has read the book, so someone else has read everything that Jen and Eric have discussed (at least up to that point).

MEGA SPOILERS

The question is, who? It could just be a random undergraduate, but that would be a rather disappointing answer. The S symbol itself is very important, and is an icon that bridges the gap between the novel The Ship of Theseus and the real world. As I understand it, S was the name of the group initially formed by Summersby, Durand, Ekstrom, VMS, and other fellow-travelers. They were authors with strong social consciences, who used what influence they had to expose the wicked and powerful; this made them enemies of dictatorships, multinational corporations, and their allies in places like the United States. At one point, they antagonized a major industrialist and arms manufacturer named Bouchard, who devoted his life and vast resources to punishing the group. Bouchard's agents appropriated the name "S" and used it to mock their opponents, slandering the writers' good names with the agents' own foul deeds. Much of The Ship of Theseus (particularly the parts set on land and the assassination chapter) is a not-at-all-thinly-veiled allegory of these events, which defined the remainder (and the very end) of VMS's life. There's a lot of confusion in the book about The S, because there are multiple and mutually hostile groups that each call themselves The S.

One thing that's said in SoT, but may or may not have been true in the real world, is that each group would use the S symbol to mark their presence and to taunt the other. It's a way of sending a message, that even here you are not safe. That being said, it seems likely that the S is from one of the S's. The question is, is it the "new" S, or the "new new" S?

If it's the modern descendents of the Bouchard faction, then, well, that would be a bad thing. We know that they're still around (though operating through subsidiaries) and very wealthy, able to fund a range of activities (including, both humorously and chillingly, compliant academic). Their motivation seems to be to erase history: to remove the records of the company's sordid past, and to intimidate people from reopening old stories; when they fail, they close those stories back up, using brutal means if necessary.

A more positive possibility, though, is that there may still be a modern group around that's descended from VMS's faction. Filomela would certainly be aligned with this side, and probably Desjardins as well. I have absolutely no way of proving this, but I would like to think that Serin is a front for this faction: they identify useful allies who share their values and outlook, and support their work, possibly eventually admitting people into their fold. I think this is referenced nicely near the end of SoT, when S sees other versions of himself and Sola piloting ships. Times change and even people change, but the underlying dynamics remain, so new people will rise to play the old roles. One day, Eric and Jen may be the new S and Sola, if they aren't already.

If that is the case, though, then who else at Pollard State University would be on "their" side? I'm tempted to say Ilsa. She appears to be one of the main antagonists early on; but based on what we see later, she seems to be pursuing her own agenda independently of Moody's. She also helps Jen graduate, when she had the power to shut her down; Ilsa also has access to the archives, and would certainly be interested in this book and very interested in the S. Even if she isn't part of Serin/Good-S, I can imagine that she might have read their notes, realized that these two kids were in love with each other, and decided to help them out. If she is in the good-S, then that would explain why Jen couldn't find Eric's recording in Moody's office: Ilsa never gave it to Moody, but instead passed it along to Serin.

Anyways! That's just a single one of the many, many threads that will doubtless provide much fodder for people to chew over for a while. I'm a big fan of the potential of ambiguity, and this book leaves tons of open questions along with many clues that suggest possible solutions, so it will keep folks busy.

The S symbol touches off an early incidence of paranoia. I thought it was interesting how the paranoia appeared to drift between the two of them: at any given point in time, one of them would often be worried about some specific thing, while the other would be reassuring them. Eric seems surprisingly calm about the fires being set around Jen and the men who are following her. Jen regularly tells Eric not to be so worried about being seen in public or to obsess over Moody. Once again, we don't get total closure here: obviously Jen was facing some sort of threat, but we never get definitive proof of who was behind it (an intriguing tossed-off suggestion from Jacob hints that Eric might be doing it, to make Jen more pliant and drive her into his arms). But, that general relationship felt very true-to-life for me; in many of my own relationships, it feels like people take "turns" needing help or giving help, and few things will make one person act stronger than another person asking for help.

The evolving relationship between Eric and Jen was surprisingly touching. Falling in love seems like such a corny concept sometimes, and can be really hard to portray well in fiction. The idea of two people falling in love just by writing marginal notes to each other seems absurd on its face. But somehow it ended up working pretty well for me: there's the shared passion in a common interest, some opposites-attracting personality differences (Jen cheerful and outgoing, Eric moody and intense), a period of gradual opening up, and eventually an intense bonding over their shared experiences. I have to admit that in some ways the oddness of their situation was what made me root for them: there's something that feels weirdly pure about two people meeting through the mind like this, so you can know the others' thoughts and hopes and fears and personality before you ever see their face. That probably hardly ever happens in real life, but it was really compelling for me in this fiction.

Very early on, Jen offers her thesis statement: that SoT is a love story. Eric scoffs initially, but by the end he comes around. I agree, but am left wondering, whose love story is it? There seem to be many possible candidates. S and Sola is an obvious one. VMS and FXC is less obvious within the text of SoT, but seems like a strong candidate based on the footnotes and codes. Really, though, isn't this book most obviously the love story of Eric and Jen? We witness the entire birth and flourishing of their love throughout the pages of the book. Late in the book, though, some additional revelations put new possibilities on the table. What about VMS and Durand? Did they have a child together? Whether the child is his or not, Signe was clearly very important to VMS: you could argue that he wrote this book, and possibly even allowed himself to be sacrificed to Bouchard's agents, to shield her from their sight. That's a very subtle sort of love, but that's kind of the point: a love so secret that it can only be found in the margins, never within the text.

I'm pretty curious about what happens to Eric and Jen at the end of the book. There are references to them leaving as soon as Jen finishes classes (even before graduation), where they apparently go someplace cold to continue their research. I think that they intend to prove that VMS was actually Vaclav Straka by traveling to Prague, hoping to uncover some records of his life before falling in the river, and maybe locating any other people from his life with whom he might have kept in touch. Incidentally, this would also involve investigating some of the awful stuff Bouchard was involved in, which will put them at continued risk.

That said... there is one place where Eric writes something like "It's cold there", except "there" is crossed out and "here" written instead. That made me think there might be an alternate explanation: Eric and Jen might have figured out that someone from the "bad" S was reading their book, and/or planned to leave the book in a place where the bad S could locate it, and deliberately planted misleading information to throw them off their trail. Based on the notes in the book, Bouchard's agents might be dispatched to Prague and spend years fruitlessly searching for them, while the heroes are actually in some other city, either continuing S's work, writing Eric's book, and/or escaping from the violence around them.

Once again, I don't know how to prove this one way or another. Late in the book, it sounds like Eric and Jen are living together in the same room, passing the same pen back and forth, writing cutely snide notes about turning down the thermostat. It wouldn't make sense to leave the book in the library stacks after that, so it must still be in their house. Right?

A couple of random notes:

Man, the horror in SoT was pretty intense! The hopelessness of their escape from the city after the wharf shooting was particularly dire. The ship itself, though, was the nexus of disturbing imagery in the book. I'm usually not very squeamish, but I found myself skipping past the descriptions of sailors (and, eventually, S) sewing their own lips shut with needle and thread. Creepy stuff!

I did find myself wondering what, exactly, the ship was supposed to be. The rest of the novel seems straightforwardly allegorical: Vevoda is Bouchard, S is Straka, the various bird-named people are members of the good S, Sola is probably Filomela, etc. So what, if anything, is the ship, and what does S's experience on the ship say about VMS in real life?

Given the very end of the book, I'm implied to think that the ship represents art. If so, that paints a very dire picture of art! S's time on board the ship is marked by relentless, painful sacrifice. He surrenders his time, becoming an old man; he loses his voice; he loses his moral compass. And, for all that, his efforts seem rather hopeless. Even when he tries to write for himself, his words are twisted into different meanings than he intended. It's a very different picture from the normal messages we hear, that art is a positive mode of expression, a way to change the world for the better. If the ship is art, SoT seems to be saying that art is painful, unappreciated, will ruin your life, and won't make a difference in the end. (I'm reminded of Kurt Vonnegut writing that the combined voices of all the novelists, filmmakers, playwrights, and musicians in America did absolutely nothing to bring the war in Vietnam to an early end.) So then, why do it? Because you must. Art, VMS seems to say, is a duty. Even if it doesn't seem to be working, and isn't having an impact, you do it because you have to.

Super-random note: I absolutely loved Maelstrom's dialogues. He speaks in revelatory malapropisms, like a character from Finnegan's Wake. It always took me a little extra time to puzzle out what he was saying, but once I did, it carried much more weight thanks to its multiplicity of meanings.

END SPOILERS

Great book! While I've compared it to House of Leaves and Pale Fire, it really is its own beast, and probably owes at least as much to the complex television-based storytelling of JJ Abrams as it does the recursively-layered literary analyses of those earlier books. (Fun side note: While JJ Abrams gets top billing for the book, the actual text was written by Doug Dorst, whose Alive in Necropolis I'd read and enjoyed five years ago. I didn't make that connection until very recently.) The book requires some attention, and I think most people will get as much out of it as they put in: if you enjoy chasing down puzzles and figuring out connections, you'll find plenty to enjoy here. Even if you "just" want to read a story, though, this is a great one, and nearly as interesting as an artifact of publishing as it is a new type of storytelling.

Loved your review! So thorough and elegantly stated, and it made me see connections I hadn't seen before. Re your idea that the ship represents art, I always thought that the ship represents the S. The 19 crew members were those in the S and could not speak as part of the Tradition--they had to keep the secret. And writing on the orlop deck represented the writers in the S who kept the "ship" afloat. It cost them their lives and their youth, but keeping the ship of the S afloat and the Tradition alive was the most important thing.

ReplyDeleteOoh, that is interesting! Since S members were represented by people on the land, I hadn't considered that they might also be part of the ship. That makes a lot of sense, though, particularly given how the crew diminishes in numbers over time much like the S during its period of persecution.

ReplyDeleteI also like the link with writing on the orlop to writing for the S, though I'm curious what significance it has that S's writing turns out "wrong". Maybe that has something to do with how the different writers had to change their style and literary voice to maintain the illusion of a single writer?